East India Company  |

| Fate | Dissolved and activities absorbed by the British Raj |

| Founded | 1600 |

| Defunct | 1858 (formally dissolved in 1873) |

| Headquarters | London |

The East India Company (also the East India Trading Company, English East India Company,[1] and then the British East India Company)[2] was an early English joint-stock company[3] that was formed initially for pursuing trade with the East Indies, but that ended up trading with the Indian subcontinent and China. The oldest among several similarly formed European East India Companies, the Company was granted an English Royal Charter, under the name Governor and Company of Merchants of London Trading into the East Indies, by Elizabeth I on 31 December 1600.[4] After a rival English company challenged its monopoly in the late 17th century, the two companies were merged in 1708 to form the United Company of Merchants of England Trading to the East Indies, commonly styled the Honourable East India Company,[5] and abbreviated, HEIC;[6] the Company was colloquially referred to as John Company,[7] and in India as Company Bahadur ("bahādur": Hindustani, lit. "brave").[8]

The East India Company traded mainly in cotton, silk, indigo dye, saltpetre, tea, and opium. However, it also came to rule large swathes of India, exercising military power and assuming administrative functions, to the exclusion, gradually, of its commercial pursuits. Company rule in India, which effectively began in 1757 after the Battle of Plassey, lasted until 1858, when, following the events of the Indian Rebellion of 1857, and under the Government of India Act 1858, the British Crown assumed direct administration of India in the new British Raj. The Company itself was finally dissolved on 1 January 1874, as a result of the East India Stock Dividend Redemption Act.

The Company long held a privileged position in relation to the English, and later the British, government. As a result, it was frequently granted special rights and privileges, including trade monopolies and exemptions. These caused resentment among its competitors, who saw unfair advantage in the Company's position. Despite this resentment, the Company remained a powerful force for over 250 years.

| Contents [hide] - 1 History

- 1.1 The foundation years

- 1.2 Foothold in India

- 1.3 Expansion

- 1.4 The road to a complete monopoly

- 1.4.1 Trade monopoly

- 1.4.2 Saltpetre trade

- 1.5 The basis for the monopoly

- 1.5.1 Colonial monopoly

- 1.5.2 Military expansion

- 1.5.3 Opium trade

- 1.6 Regulation of the company's affairs

- 1.6.1 Financial troubles

- 1.6.2 Regulating Acts

- 1.6.2.1 East India Company Act 1773

- 1.6.2.2 East India Company Act (Pitt's India Act) 1784

- 1.6.2.3 Act of 1786

- 1.6.2.4 Charter Act 1813

- 1.6.2.5 Charter Act 1833

- 1.6.2.6 Charter Act 1853

- 1.7 Indian Rebellion of 1857-8

- 1.8 Impact

- 2 Legacy

- 3 East India Club

- 4 Flags

- 5 Ships

- 6 East India Company records

- 7 See also

- 8 Notes

- 9 References

- 10 External links

|

[edit] History

[edit] The foundation years

Soon after the defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588, a group of merchants of London presented a petition to Queen Elizabeth I for permission to sail to the Indian Ocean.[9] The permission was granted and in 1591 three ships sailed from England, around the Cape of Good Hope, to the Arabian Sea; one of them, the Edward Bonaventure then sailed around Cape Comorin and on to the Malay Peninsula, and subsequently returned to England in 1594.[9] In 1596, three more ships sailed out east, however, these were all lost at sea.[9] Two years later, on September 24, 1599, another group of merchants of London, having raised £30,133 in capital, met to form a corporation. Although their first attempt was unsuccessful, they nonetheless set about seeking the Queen's unofficial approval, purchased ships for their venture, increased their capital to £68,373, and convened again a year later.[9] This time they succeeded, and on December 31, 1600, the last day of the sixteenth century, the Queen granted a Royal Charter to "George, Earl of Cumberland, and 215 Knights, Aldermen, and Burgesses" under the name, Governor and Company of Merchants of London trading with the East Indies.[10] The charter awarded the newly formed company, for a period of fifteen years, a monopoly of trade with all countries to the east of the Cape of Good Hope and to the west of the Straits of Magellan.[10] Sir James Lancaster commanded the first East India Company voyage in 1601.[11]

Initially, the Company struggled in the spice trade due to the competition from the already well established Dutch. However the Company did open a factory (as the trading posts were known) in Bantam on the first voyage and imports of pepper from Java were an important part of the Company's trade for twenty years. The factory in Bantam was finally closed in 1683. During this time ships belonging to the company arrived in India, docking at Surat, which was established as a trade transit point in 1608. In the next two years, it managed to build its first factory in the town of Machilipatnam on the Coromandel Coast of the Bay of Bengal. The high profits reported by the Company after landing in India (presumably owing to a reduction in overhead costs affected by the transit points), initially prompted King James I to grant subsidiary licenses to other trading companies in England. But, in 1609, he renewed the charter given to the Company for an indefinite period, including a clause which specified that the charter would cease to be in force if the trade turned unprofitable for three consecutive years.

The Company was led by one Governor and 24 directors who made up the Court of Directors. They were appointed by, and reported to, the Court of Proprietors. The Court of Directors had ten committees reporting to it.

[edit] Foothold in India

English traders frequently engaged in hostilities with their Dutch and Portuguese counterparts in the Indian Ocean. The Company achieved a major victory over the Portuguese in the Battle of Swally in 1612. Perhaps realizing the cost of waging trade wars in remote seas, the Company decided to explore the feasibility for gaining a territorial foothold in mainland India, with official sanction of both countries, and requested the Crown to launch a diplomatic mission. In 1615, Sir Thomas Roe was instructed by James I to visit the Mughal Emperor Nuruddin Salim Jahangir (r. 1605 - 1627) to arrange for a commercial treaty which would give the Company exclusive rights to reside and build factories in Surat and other areas. In return, the Company offered to provide the Emperor with goods and rarities from the European market. This mission was highly successful as Jahangir sent a letter to James through Sir Thomas Roe:

- "Upon which assurance of your royal love I have given my general command to all the kingdoms and ports of my dominions to receive all the merchants of the English nation as the subjects of my friend; that in what place soever they choose to live, they may have free liberty without any restraint; and at what port soever they shall arrive, that neither Portugal nor any other shall dare to molest their quiet; and in what city soever they shall have residence, I have commanded all my governors and captains to give them freedom answerable to their own desires; to sell, buy, and to transport into their country at their pleasure.

- For confirmation of our love and friendship, I desire your Majesty to command your merchants to bring in their ships of all sorts of rarities and rich goods fit for my palace; and that you be pleased to send me your royal letters by every opportunity, that I may rejoice in your health and prosperous affairs; that our friendship may be interchanged and eternal."[12]

[edit] Expansion

The Company, benefiting from the imperial patronage, soon expanded its commercial trading operations, eclipsing the Portuguese Estado da India, which had established bases in Goa, Chittagong and Bombay (which was later ceded to England as part of the dowry of Catherine de Braganza). The Company created trading posts in Surat (where a factory was built in 1612), Madras (1639), Bombay (1668) and Calcutta (1690). By 1647, the Company had 23 factories, each under the command of a factor or master merchant and governor if so chosen, and 90 employees in India. The major factories became the walled forts of Fort William in Bengal, Fort St George in Madras and the Bombay Castle.

In 1634, the Mughal emperor extended his hospitality to the English traders to the region of Bengal (and in 1717 completely waived customs duties for the trade). The company's mainstay businesses were by now in cotton, silk, indigo dye, saltpetre and tea. All the while, it was making inroads into the Dutch monopoly of the spice trade in the Malaccan straits, which the Dutch had acquired by ousting the Portuguese in 1640-41. In 1711, the Company established a trading post in Canton (Guangzhou), China, to trade tea for silver. In 1657, Oliver Cromwell renewed the charter of 1609, and brought about minor changes in the holding of the Company. The status of the Company was further enhanced by the restoration of monarchy in England. By a series of five acts around 1670, King Charles II provisioned it with the rights to autonomous territorial acquisitions, to mint money, to command fortresses and troops and form alliances, to make war and peace, and to exercise both civil and criminal jurisdiction over the acquired areas.

[edit] The road to a complete monopoly

[edit] Trade monopoly

| | This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding reliable references (ideally, using inline citations). Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (May 2008) |

The prosperity that the employees of the company enjoyed allowed them to return to their country and establish sprawling estates and businesses, and to obtain political power. Consequently, the Company developed for itself a lobby in the English parliament. However, under pressure from ambitious tradesmen and former associates of the Company (pejoratively termed Interlopers by the Company), who wanted to establish private trading firms in India, a deregulating act was passed in 1694. This allowed any English firm to trade with India, unless specifically prohibited by act of parliament, thereby annulling the charter that was in force for almost 100 years. By an act that was passed in 1698, a new "parallel" East India Company (officially titled the English Company Trading to the East Indies) was floated under a state-backed indemnity of £2 million. However, the powerful stockholders of the old company quickly subscribed a sum of £315,000 in the new concern, and dominated the new body. The two companies wrestled with each other for some time, both in England and in India, for a dominant share of the trade. However, it quickly became evident that, in practice, the original Company faced scarcely any measurable competition. Both companies finally merged in 1708, by a tripartite indenture involving them both as well as the state. Under this arrangement, the merged company lent to the Treasury a sum of £3,200,000, in return for exclusive privileges for the next three years, after which the situation was to be reviewed. The amalgamated company became the United Company of Merchants of England Trading to the East Indies.[citation needed]

In the following decades there was a constant see-saw battle between the Company lobby and the Parliament. The Company sought a permanent establishment, while the Parliament would not willingly allow it greater autonomy, and so relinquish the opportunity to exploit the Company's profits. In 1712, another act renewed the status of the Company, though the debts were repaid. By 1720, 15% of British imports were from India, almost all passing through the Company, which reasserted the influence of the Company lobby. The license was prolonged until 1766 by yet another act in 1730.

At this time, Britain and France became bitter rivals. Frequent skirmishes between them took place for control of colonial possessions. In 1742, fearing the monetary consequences of a war, the British government agreed to extend the deadline for the licensed exclusive trade by the Company in India until 1783, in return for a further loan of £1 million. The skirmishes did escalate to the feared war. Between 1756 and 1763, the Seven Years' War diverted the state's attention towards consolidation and defence of its territorial possessions in Europe and its colonies in North America. The war also took place on Indian soil, between the Company troops and the French forces. In 1757, the Law Officers of the Crown delivered the Pratt-Yorke opinion distinguishing overseas territories acquired by conquest from those acquired by private treaty. The opinion asserted that, while the Crown of Great Britain enjoyed sovereignty over both, only the property of the former was vested in the Crown.[13]

With the advent of the Industrial Revolution, Britain surged ahead of its European rivals. Demand for Indian commodities was boosted by the need to sustain the troops and the economy during the war, and by the increased availability of raw materials and efficient methods of production. As home to the revolution, Britain experienced higher standards of living. Its spiralling cycle of prosperity, demand and production had a profound influence on overseas trade. The Company became the single largest player in the British global market. It reserved for itself an unassailable position in the decision-making process of the Government.

William Pyne notes in his book The Microcosm of London (1808) that

- "On the 1 March 1801, the debts of the East India Company to £5,393,989 their effects to £15,404,736 and their sales increased since February 1793, from £4,988,300 to £7,602,041."

[edit] Saltpetre trade

Sir John Banks, a businessman from Kent who negotiated an agreement between the King and the Company, began his career in a syndicate arranging contracts for victualling the navy, an interest he kept up for most of his life. He knew Pepys and John Evelyn and founded a substantial fortune from the Levant and Indian trades. He also became a Director and later, as Governor of the East Indian Company in 1672, he was able to arrange a contract which included a loan of £20,000 and £30,000 worth of saltpetre for the King 'at the price it shall sell by the candle'[citation needed] - that is by auction - where an inch of candle burned and as long as it was alight bidding could continue. The agreement also included with the price 'an allowance of interest which is to be expressed in tallies.'[citation needed] This was something of a breakthrough in royal prerogative because previous requests for the King to buy at the Company's auctions had been turned down as 'not honourable or decent.'[citation needed] Outstanding debts were also agreed and the Company permitted to export 250 tons of saltpetre. Again in 1673, Banks successfully negotiated another contract for 700 tons of saltpetre at £37,000 between the King and the Company. So urgent was the need to supply the armed forces in the United Kingdom, America and elsewhere that the authorities sometimes turned a blind eye on the untaxed sales. One governor of the Company was even reported as saying in 1864 that he would rather have the saltpetre made than the tax on salt.[14]

[edit] The basis for the monopoly

[edit] Colonial monopoly

Robert Clive, 1st Baron Clive, became the first British Governor of Bengal.

The Seven Years' War (1756 – 1763) resulted in the defeat of the French forces and limited French imperial ambitions, also stunting the influence of the industrial revolution in French territories. Robert Clive, the Governor General, led the Company to an astounding victory against Joseph François Dupleix, the commander of the French forces in India, and recaptured Fort St George from the French. The Company took this respite to seize Manila[15] in 1762. By the Treaty of Paris (1763), the French were allowed to maintain their trade posts only in small enclaves in Pondicherry, Mahe, Karikal, Yanam, and Chandernagar without any military presence. Although these small outposts remained French possessions for the next two hundred years, French ambitions on Indian territories were effectively laid to rest, thus eliminating a major source of economic competition for the Company. In contrast, the Company, fresh from a colossal victory, and with the backing of a disciplined and experienced army, was able to assert its interests in the Carnatic from its base at Madras and in Bengal from Calcutta, without facing any further obstacles from other colonial powers.[citation needed]

[edit] Military expansion

Main article: Company rule in India

The Company continued to experience resistance from local rulers during its expansion. Robert Clive led company forces against Siraj Ud Daulah, the last independent Nawab of Bengal, Bihar and Orissa to victory at the Battle of Plassey in 1757, resulting in the conquest of Bengal. This victory estranged the British and the Mughals, since Siraj Ud Daulah was a Mughal feudatory ally. But the Mughal empire was already on the wane after the demise of Aurangzeb, and was breaking up into pieces and enclaves. After the Battle of Buxar, Shah Alam II, the ruling emperor, gave up the administrative rights over Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa. Clive thus became the first British Governor of Bengal.

Haidar Ali and Tipu Sultan, the legendary rulers of Mysore (in Carnatic), gave a tough time to the British forces. Having sided with the French during the war, the rulers of Mysore continued their struggle against the Company with the four Anglo-Mysore Wars. Mysore finally fell to the Company forces in 1799, with the slaying of Tipu Sultan.

With the gradual weakening of the Maratha empire in the aftermath of the three Anglo-Maratha wars, the British also secured Bombay and the surrounding areas. It was during these campaigns, both against Mysore and the Marathas, that Arthur Wellesley, later Duke of Wellington, first showed the abilities which would lead to victory in the Peninsular War and at the Battle of Waterloo. A particularly notable engagement involving forces under his command was the Battle of Assaye. Thus, the British had secured the entire region of Southern India (with the exception of small enclaves of French and local rulers), Western India and Eastern India.

The last vestiges of local administration were restricted to the northern regions of Delhi, Oudh, Rajputana, and Punjab, where the Company's presence was ever increasing amidst the infighting and dubious offers of protection against each other. Coercive action, threats and diplomacy aided the Company in preventing the local rulers from putting up a united struggle against it. The hundred years from the Battle of Plassey in 1757 to the Sepoy Mutiny of 1857 were a period of consolidation for the Company, which began to function more as a nation and less as a trading concern.

The first cholera pandemic began in Bengal, then spread across India by 1820. 10,000 British troops and countless Indians died during this pandemic.[16] Between 1736 and 1834 only some 10% of East India Company's officers survived to take the final voyage home.[17]

[edit] Opium trade

Main article: Opium Wars

In the eighteenth century, Britain had a huge trade deficit with Qing Dynasty China and so in 1773, the Company created a British monopoly on opium buying in Bengal. As opium trade was illegal in China, Company ships could not carry opium to China. So the opium produced in Bengal was sold in Calcutta on condition that it be sent to China.[18]

Despite the Chinese ban on opium imports, reaffirmed in 1799, it was smuggled into China from Bengal by traffickers and agency houses (such as Jardine, Matheson and Company, Ltd.) averaging 900 tons a year. The proceeds from drug-runners at Lintin Island were paid into the Company’s factory at Canton and by 1825, most of the money needed to buy tea in China was raised by the illegal opium trade. In 1838, with opium smuggling approaching 1400 tons a year, the Chinese imposed a death penalty on opium smuggling and sent a new governor, Lin Zexu to curb smuggling. This finally resulted in the First Opium War, eventually leading to the British seizure of Hong Kong and the opening of the Chinese market to British drug traffickers.

[edit] Regulation of the company's affairs

Monopolistic activity by the company triggered the Boston Tea Party.

[edit] Financial troubles

Though the Company was becoming increasingly bold and ambitious in putting down resisting states, it was getting clearer day by day that the Company was incapable of governing the vast expanse of the captured territories. The Bengal famine, in which one-third of the local population died, set the alarm bells ringing back home. Military and administrative costs mounted beyond control in British administered regions in Bengal due to the ensuing drop in labour productivity. At the same time, there was commercial stagnation and trade depression throughout Europe following the lull in the post-Industrial Revolution period. The desperate directors of the company attempted to avert bankruptcy by appealing to Parliament for financial help. This led to the passing of the Tea Act in 1773, which gave the Company greater autonomy in running its trade in America, and allowed it an exemption from the tea tax—which its colonial competitors were required to pay. When the American colonists, who included tea merchants, were told of the act, they tried to boycott it, claiming that, although the price had gone down on the tea when enforcing the act, it was a tax all the same, and the king should not have the right to just have a tax for no apparent reason. The arrival of tax-exempt Company tea, undercutting the local merchants, triggered the Boston Tea Party in the Province of Massachusetts Bay, one of the major events leading up to the American Revolution.

[edit] Regulating Acts

[edit] East India Company Act 1773

By this Act (13 Geo. III, c. 63), the Parliament of Great Britain imposed a series of administrative and economic reforms and by doing so clearly established its sovereignty and ultimate control over the Company. The Act recognized the Company's political functions and clearly established that the "acquisition of sovereignty by the subjects of the Crown is on behalf of the Crown and not in its own right."

Despite stiff resistance from the East India lobby in parliament, and from the Company's shareholders, the Act was passed. It introduced substantial governmental control, and allowed the land to be formally under the control of the Crown, but leased to the Company at £40,000 for two years. Under this provision, the governor of Bengal Warren Hastings was promoted to the rank of Governor General, having administrative powers over all of British India. It provided that his nomination, though made by a court of directors, should in future be subject to the approval of a Council of Four appointed by the Crown - namely Lt. General John Clavering, George Monson, Richard Barwell and Philip Francis. He was entrusted with the power of peace and war. British judicial personnel would also be sent to India to administer the British legal system. The Governor General and the council would have complete legislative powers. Thus, Warren Hastings became the first Governor-General of India. The company was allowed to maintain its virtual monopoly over trade, in exchange for the biennial sum and an obligation to export a minimum quantity of goods yearly to Britain. The costs of administration were also to be met by the company. These provisions, initially welcomed by the Company, backfired. The Company had an annual burden on its back, and its finances continued steadily to decline.[19]

[edit] East India Company Act (Pitt's India Act) 1784

The India Act of 1784 (24 Geo. III, s. 2, c. 25) had two key aspects:

- Relationship to the British government: the bill differentiated the East India Company's political functions from its commercial activities. In political matters the East India Company was subordinated to the British government directly. To accomplish this, the Act created a Board of Commissioners for the Affairs of India, usually referred to as the Board of Control. The members of the Board were the Chancellor of the Exchequer, a Secretary of State, and four Privy Councillors, nominated by the King. The act specified that the Secretary of State "shall preside at, and be President of the said Board".

- Internal Administration of British India: the bill laid the foundation for the centralized and bureaucratic British administration of India which would reach its peak at the beginning of the twentieth century during the governor-generalship of George Nathaniel Curzon, 1st Baron Curzon.

The expanded East India House, Leadenhall Street, London, as rebuilt 1799-1800, Richard Jupp, architect (as seen c. 1817; demolished in 1929)

Pitt's Act was deemed a failure because it quickly became apparent that the boundaries between government control and the company's powers were nebulous and highly subjective. The government also felt obliged to respond to humanitarian calls for better treatment of local peoples in British-occupied territories. Edmund Burke, a former East India Company shareholder and diplomat, was moved to address the situation and introduced a new Regulating Bill in 1783. The bill was defeated, however, due to intense lobbying by company loyalists and accusations of nepotism in the bill's recommendations for the appointment of councillors.

[edit] Act of 1786

This Act (26 Geo. III c. 16) enacted the demand of Lord Cornwallis, that the powers of the Governor-General be enlarged to empower him, in special cases, to override the majority of his Council and act on his own special responsibility. The Act also enabled the offices of the Governor-General and the Commander-in-Chief to be jointly held by the same official.

This Act clearly demarcated borders between the Crown and the Company. After this point, the Company functioned as a regularized subsidiary of the Crown, with greater accountability for its actions and reached a stable stage of expansion and consolidation. Having temporarily achieved a state of truce with the Crown, the Company continued to expand its influence to nearby territories through threats and coercive actions. By the middle of the 19th century, the Company's rule extended across most of India, Burma, Malaya, Singapore and Hong Kong, and a fifth of the world's population was under its trading influence.

[edit] Charter Act 1813

The aggressive policies of Lord Wellesley and the Marquis of Hastings led to the Company gaining control of all India, except for the Punjab, Sind and Nepal. The Indian Princes had become vassals of the Company. But the expense of wars leading to the total control of India strained the Company’s finances to the breaking point. The Company was forced to petition Parliament for assistance. This was the background to the Charter Act of 1813 (53 Geo. III c. 155) which, among other things:

- asserted the sovereignty of the British Crown over the Indian territories held by the Company;

- renewed the Charter of Company for a further twenty years but,

- deprived the Company of its Indian trade monopoly except for trade in tea and the trade with China;

- required the Company to maintain separate and distinct its commercial and territorial accounts; and,

- opened India to missionaries.

[edit] Charter Act 1833

The Industrial Revolution in Britain, and the consequent search for markets, and the rise of laissez-faire economic ideology form the background to this act. The Act:

- removed the Company's remaining trade monopolies and divested it of all its commercial functions;

- renewed for another twenty years the Company’s political and administrative authority;

- invested the Board of Control with full power and authority over the Company. As stated by Kapur Professor Sri Ram Sharma, thus, summed up the point: "The President of the Board of Control now became Minister for Indian Affairs";

- carried further the ongoing process of administrative centralization through investing the Governor-General in Council with, full power and authority to superintend and, control the Presidency Governments in all civil and military matters;

- initiated a machinery for the codification of laws;

- provided that no Indian subject of the Company would be debarred from holding any office under the Company by reason of his religion, place of birth, descent or colour. However, this remained a dead letter well into the 20th century;

- vested the Island of St Helena in the Crown.

Meanwhile, British influence continued to expand; in 1845, the Danish colony of Tranquebar was sold to Great Britain. The Company had at various stages extended its influence to China, the Philippines, and Java. It had solved its critical lack of the cash needed to buy tea by exporting Indian-grown opium to China. China's efforts to end the trade led to the First Opium War with Britain.

[edit] Charter Act 1853

This Act provided that British India would remain under the administration of the Company in trust for the Crown until Parliament should decide otherwise.

[edit] Indian Rebellion of 1857-8

Main article: Indian Rebellion of 1857

The Indian Rebellion of 1857, known to the British as the "Great Mutiny", but to Indians as the "First War of Independence", resulted in widespread devastation in India and condemnation of the Company for permitting the events to occur. One of the consequences was that the British government nationalized the Company. The Company lost all its administrative powers; its Indian possessions, including its armed forces, were taken over by the Crown pursuant to the provisions of the Government of India Act 1858.

The Company continued to manage the tea trade on behalf of the British government (and the supply of Saint Helena) until the East India Stock Dividend Redemption Act came into effect, on 1 January 1874, under the terms of which the Company was dissolved.[20]

[edit] Impact

| | This section does not cite any references or sources. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources (ideally, using inline citations). Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (November 2007) |

| | The neutrality of this section is disputed. Please see the discussion on the talk page. Please do not remove this message until the dispute is resolved. (September 2008) |

As a trading body, the first remit of the Company was to maximise its profits and with taxation rights the profits to be obtained from Bengal came from land tax as well as trade tariffs. As lands came under company control, the land tax was typically raised by 5 times what it had been – from 10% to up to 50% of the value of the agricultural produce.[citation needed] In the first years of the rule of the British East India Company, the total land tax income was doubled and most of this revenue flowed out of the country. As the famine approached its height in April of 1770, the Company announced that the land tax for the following year was to be increased by a further 10%.[citation needed]

The company has also been criticised for forbidding the "hoarding" of rice. This prevented traders and dealers from laying in reserves that in other times would have tided the population over lean periods, as well as ordering the farmers to plant indigo instead of rice.[citation needed]

By the time of the famine, monopolies in grain trading had been established by the Company and its agents. The Company had no plan for dealing with the grain shortage, and actions were only taken insofar as they affected the mercantile and trading classes. Land revenue decreased by 14% during the affected year, but recovered rapidly (Kumkum Chatterjee). According to McLane, the first governor-general of British India, Warren Hastings, acknowledged "violent" tax collecting after 1771: revenues earned by the Company were higher in 1771 than in 1768. Globally, the profit of the Company increased from 15 million rupees in 1765 to 30 million rupees in 1777.[citation needed]

The Company also had interests along the routes to India from Great Britain. As early as 1620, the company attempted to lay claim to the Table Mountain region in South Africa; later it occupied and ruled St Helena. Piracy was a severe problem for the Company. This problem reached its peak in 1695, when pirate Henry Avery captured the Great Mughal's treasure fleet. The Company was held responsible for that raid, because according to Indian popular opinion of the time, all pirates were by definition English. Later, the Company unsuccessfully employed Captain Kidd to combat piracy in the Indian Ocean; it also cultivated the production of tea in India. Other notable events in the Company's history were that it held Napoleon captive on St Helena, and made the fortune of Elihu Yale. Its products were the basis of the Boston Tea Party in Colonial America.[citation needed]

Its shipyards provided the model for Saint Petersburg. Elements of its administration, the Honourable East India Company Civil Service (HEICS), survive in the Indian Administrative Service (IAS), the successor to the Indian Civil Service (ICS). Its corporate structure was the most successful early example of a joint stock company. The demands of Company officers on the treasury of Bengal contributed tragically to the province's incapacity in the face of a famine, which killed millions of people in 1770-1773.[citation needed]

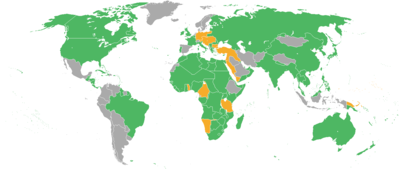

British and other European settlements in India

The company was an aggressive party and destroyed monasteries in Tibet. It helped cause the Opium Wars as a promoter of opium smuggling. With these actions, the company diminished the popularity of England and Europeans in Tibet and China.[citation needed]

[edit] Legacy

The East India Company has had a long lasting impact on the Indian Subcontinent, although dissolved following the rebellion of 1857, it stimulated the growth of the British Empire. Its armies after 1857 were to become the armies of British India and it played a key role in replacing the official language of India from Persian to English. Even today the English language has official status in Pakistan and India, being used by the government and civil service. Some phrases introduced by the company are considered to be archaic in British English today, such as do the needful, but live on in the English of South Asia and are used daily.[21]

[edit] East India Club

The East India Club in London was formed in 1849 for officers of the East India Company. The Club still exists today as a private Gentlemen's Club and its club house is situated at 16, St. James's Square, London.

[edit] Flags

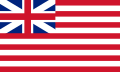

| | | | |

National Geographic (1917) | Prior to the Acts of Union which created the Kingdom of Great Britain, the flag contained the St George's Cross in the canton representing the Kingdom of England. | The flag had a Union Flag in the canton after the creation of the Kingdom of Great Britain in 1707. | After 1801 the flag contains the Union Flag of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland in the canton.(1810) |

The East India Company flag changed over time. From the period of 1600 to 1707 (Act of Union between England and Scotland) the flag consisted of a St George's cross in the canton and a number of alternating Red and White stripes. After 1707 the canton contained the original Union Flag consisting of a combined St George's cross and a St Andrew's cross. After the Act of Union 1800, that joined Ireland into the United Kingdom, the canton of the East India Company's flag was altered accordingly to include the new Union Flag with the additional St Patrick's cross. There has been much debate and discussion regarding the number of stripes on the flag and the order of the stripes. Historical documents and paintings show many variations from 9 to 13 stripes, with some images showing the top stripe being red and others showing the top stripe being white.

At the time of the American Revolution the East India Company flag would have been identical to the Grand Union Flag. The flag probably inspired the Stars and Stripes (as argued by Sir Charles Fawcett in 1937).[22] Comparisons between the Stars and Stripes and the Company's flag from historical records present some convincing arguments. The John Company flag dates back to the 1600s whereas the United States adopted the Stars and Stripes in 1777.[23]

The stripes and gridlike appearance of the flag gave rise to several pieces of imperial slang. Most notably is the phrase 'riding the gridiron'; this referred to travelling on a ship flying the company flag to / from India.

[edit] Ships

A ship of the East India Company can also be called an East Indiaman.

- Earl of Abergavenny

- Royal Captain

- Agamemnon (1855)

[edit] East India Company records

Unlike all other British Government records, the records from the East India Company (and its successor the India Office) are not in The National Archives at Kew, London, but are stored by the British Library in London as part of the Asia, Pacific and Africa Collection. The catalogue is searchable online in the Access to Archives catalogues.[24] Many of the East India Company records are freely available online under an agreement that FIBIS have with the British Library.